Why the Creek's drying up

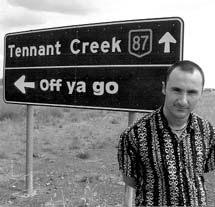

Richard Di Natale has finished his tour

of duty as a doctor at

Anyinginyi Congress. He stopped on his way out of town

to give us his diagnosis of Tennant's ills.

It is one of the most isolated towns in Australia. Around three thousand

people live in this flat, dusty and inconceivably remote place. The

nearest capital city is Darwin, about 1000km away and the cost of a

flight to most other capital cities equates with a trip overseas. To

call this town inhospitable is an understatement. With summer temperatures

that are more suited to baking cakes than supporting human life and

a winter that produces little or no rain one would not expect Tennant

Creek to feature prominently in most real estate guides.

Yet somehow the people who live here manage to eke out an existence.

In fact some of them positively thrive in this atmosphere of red dust,

heat haze and spinifex and they remain defiant in a global environment

that seems to have no regard for the people of the bush.

Originally built on the back of the mining and pastoral industries the

fate of Tennant Creek, like so many other towns like it, hangs in the

balance. Its population is made up of a large indigenous base, a transient

population and a shrinking number of 'locals'.

Visitors like myself arrive on short to medium term contracts and work

largely within education, health, and other smaller government sectors

and we eventually move on within a few years. The term local is used

a little more loosely here than in other places and is could be applied

to the group of residents who have a stronger connection with the town

than just their work.

Over recent years many of these long-term residents have been feeling

a little uneasy. A quantum shift is occurring within the town that is

challenging their very existence. A town that previously existed because

of what lay beneath the ground rather than what lay on top of it has

been forced to adapt to a sobering reality. Tennant Creek is no longer

a mining town.

In fact there are no operating mines within the region for the first

time in the town's history. The change reflects a global shift away

from old economy stocks to the booming hi-tech sector, a change that

has inflicted near fatal wounds on the commodities markets. Even though

the stockmarket is a volatile beast that can take unexpected turns,

the future for mining in Tennant Creek remains grim. An unexpected recovery

in the mining sector will probably not impact significantly on the town

as mining companies now prefer to fly their contractors into operating

mines on a rotational basis.

The residents now live in a town that exists because of and not despite

its indigenous community. Without it the town's economy would collapse.

Julalikari Council is easily the biggest employer in town with a payroll

of several hundred employees. Anyinginyi Congress has an annual operating

budget of almost four million dollars.

Local businesses are now reliant on the income from the indigenous community

and without it the town would no longer exist. Hence the dilemma. Suddenly

a reality that many people refused to acknowledge is now the source

of their very existence. A town that previously relied on the right

to mine land is now confronted with land rights. Businesses that once

had to deal with reconciling accounts now have to deal with reconciliation.

Members of the community have developed their own very different measures

for coping with this shift in the town's demographics. There are those

who revel in a new culture that is infinitely complex and ancient. There

are others who have somehow managed to remain insulated from this confronting

sector of their town.

And there are those who thrive on the limitless opportunities to exploit

and misappropriate. For these people Tennant Creek is still a gold mine.

Over the years they have developed clandestine schemes that have contributed

to the Territory's reputation for corruption and exploitation. The town's

list of dubious enterprises is lengthy.

A transport service operates a mobile banking service complete with

collection of customer bankcards. A retailer cashes personal cheques

under the proviso that a significant proportion of the cash is spent

on their high-priced goods. There is also the peculiar situation of

a nightclub that actually opens at midday, against the spirit of alcohol

restrictions designed to reduce alcohol consumption and minimise associated

harm.

The indigenous organisations of Tennant Creek are also struggling to

deal with this new reality. Circumstances would suggest that this new

economic reliance on the indigenous community would allow them to occupy

a powerful position within the town's political spectrum. Yet they are

still striving to grasp this opportunity. In the recent past these organisations

were strong, united and progressive voices in the fight for change.

Issues like the fight to implement alcohol restrictions seemed to signify

a movement toward real independence and galvanised a groundswell of

community support. But many of the strong voices of the past are now

silent, muffled by years of frustration and burnt out by life in a town

where the odds are stacked against them. They already have much to be

proud of but strong leadership and innovation are needed now.

The Community Development Employment Program and the burgeoning arts

industry could be developed further, progressive initiatives such as

recycling could be resurrected and opportunities in areas such as indigenous

tourism could be explored. Creative alternatives such as the family

income scheme proposed in Cape York by Noel Pearson need to be considered

to counter some of the destructive effects of welfare and royalty payments

and to demonstrate to the entire community that this is a shared problem

with shared responsibilities.

Education, or lack of it, remains one of the most obvious and fundamental

issues in Tennant Creek. An environment exists where indigenous children

are simply not achieving the necessary standards of literacy and numeracy

necessary to function in an increasingly complex society. The reasons

are multiple and involved but almost certainly reflect a failure in

current educational models.

This cohort of adolescents is already showing evidence of becoming increasingly

marginalised and the signs are worrying. The emergence of American ghetto

culture is a new feature in the landscape of Tennant Creek. Gangs with

names such as Westside and Boys in Black are embracing the clothes,

the gestures and now the violence that forms the fabric of parts of

American society.

Unless the educational environment for indigenous students becomes more

appropriate this will only get worse. Total integration into mainstream

classes still remains a threatening prospect for many indigenous children

and alternative models could be explored.

At the core of many of these issues is a paradox. Those people who resent

the 'handouts' and special privileges given to the indigenous community

and believe that social justice should not be a core part of economic

policy now find their own dire economic circumstances have come about

from this very ideology. This zealous pursuit of a free market agenda

at the expense of all else is pursued fervently by politicians across

the political spectrum and has strangled rural Australia almost universally.

The recent exodus from Tennant Creek is a direct result of a dogma where

competition is a sacred cow to be protected at all costs and profits

are pursued single-mindedly in the name of improved efficiency.

But it is an ideology that is fundamentally flawed and based on false

assumptions. Conservative politicians can no longer profess to support

'family values' while maintaining their current obsession with free

trade and economic rationalism because the two ideologies are no longer

compatible.

Sadly most of these problems seem to be ignored by those groups within

the town who could otherwise be catalysts for change. The town boasts

a newspaper whose content is bland and predictable. It has missed most

opportunities to debate serious issues in any detail and this has greatly

diminished its influence.

The Regional Tourist Association promotes the town almost entirely on

the basis of its mining heritage. They have shown little interest in

promoting indigenous culture or utilising local resources, an approach

that is counterproductive for both social and economic reasons.

The Barkly Blueprint, a document that was developed by a narrow cross

section of the community, offers little hope for a town that is in such

obvious need. Reliance on short-term projects like the railway and refusing

to incorporate indigenous issues into the mainstream agenda continues

to demonstrate a distinct lack of vision.

Tennant Creek is at the crossroads. It has the potential to become a

vibrant and prosperous town, an example of living reconciliation that

offers a unique cultural experience to both visitors and locals. But

it could also become a symbol of this nation's shame. The choice is

yours.