It was the strongest magnitude earthquake

Australia

has recorded in recent history. It struck Tennant Creek

at 10:06 am on Friday 22nd January 1988

Les Liddell was going about his business

moving things

from place to place when without warning they all

started to move by themselves

Suddenly there were the first shocks. I

was at work in the office talking to a chap and while we were talking

there it just sounded like a rumbling coming down the fence. We did

have six big mining tanks stored in our major yard and it sounded like

a roadtrain had hit these tanks.

I thought, "My God, what's happened?" We all ran outside to

have a look at what this clanging and banging was, and it was actually

the earth shaking.

It was the first indication that something was happening. It took us

probably ten seconds to realise it was an earthquake and not just a

truck hitting something.

It trembled from the south-west to the north-east and it lasted for

forty-five seconds. This was probably the longest forty-five seconds

I've ever stood there and shook, we couldn't do anything, except just

watch windows rattle and poles shake.

It was like a thunder roll - you could hear it come and hear it go,

and there was a little "crack" in the middle of it as it went

past you, and then it rolled away.

That was the first part of the earthquake.

I immediately tried to ring Alice Springs Emergency Services to advise

them that we'd had an earthquake, but all phones were jammed. As everyone

tried to ring up everyone else to see what went wrong the whole automatic

exchange jammed up completely, which meant we had no communications

for about an hour. So we had to use radio to contact Alice to advise

them of our situation.

A quick run round town showed there was no actual damage, except some

of the people were still shaking a bit! Some said it didn't worry them,

others said it affected them a little bit, but the ones in the double-storey

buildings in the main street fled their top storey because they did

really shake. That was as a result of the first tremor.

The second tremor came at about two-thirty that afternoon. I was back

over in my residential address by then, and I was standing at the front

door of my office when it hit. It had the same intensity as the first

one for about thirty seconds, and then it stepped up into a much higher

magnitude of intensity. It shook twice as hard.

The power poles out the front - the light poles on the median strip

- were actually swinging about ten to twelve feet sideways; the concrete

kerbing was going up and down like an ocean; and we stood with our feet

apart trying to keep our balance.

You just stood there in complete shock - rooted to the spot and watched

it happen in front of you. You could not believe what was happening,

you even couldn't talk after it. It took you a couple of minutes to

be able to talk again. It's a shock that hits the system. Your voice

is raised - the anxiety in your voice - you can hear it. If you were

recording it, you would hear very clearly that you are talking at a

different stress level.

Following this shock, when we toured the town we found that in the supermarket

it had shaken all the cans off their shelves onto the floor. The supermarket

had to close for two hours while it re-stacked its shelves.

It took the power out this time, it shook the automatic cut-outs at

the power station - it shook them out of their cabinets so the turbines

automatically shut down. So we had no power.

Damage was still limited to mainly shock to people, that it could occur.

I think the caravan park had a big air-conditioner shaken off the wall.

A few cracks had appeared in quite a few of the brick buildings, and

a lot of the concrete kerbing and footpaths - every slab had cracked

across the middle from this shaking.

We had our small committee operational at the police station and so

we went immediately back to the police station. We still weren't able

to determine where the epicentre was at this stage. We knew it was coming

from the south-west, but we didn't know how far out. We were virtually

waiting on the seismology station fellows to come in and give us a bit

of an indication. They came in at five o'clock and we talked to them,

but they said they couldn't tell us because it had shaken all their

equipment loose! The recordings would have to come from Townsville or

somewhere far away where it was less intense.

But there was an earth fault out about 14 km south-west of Tennant Creek,

and they did actually have a bloke out there who, when he came back,

said all the anthills were leaning over, all in one direction. I said,

"Well, that's where the fault line is, it's in that area, but we

need to pinpoint it".

By six o'clock I'd gone back to normal working practice and we were

just getting ready to send our aircraft away on the southern nightly

run with the courier services, when the Chief Minister arrived from

Darwin with his entourage of reporters and staff.

The first thing they did was to ask me what was actually going on at

the airport. I told them that we'd had two major quakes, and we were

having intermediate shakes every few minutes.

At ten o'clock that night we got the really big shake, while the Chief

Minister, Steve Hatton, was here.

Believe me, it really shook!

I stood at my front door and watched my two Falcons shifting three foot

sideways, criss-crossing one another, and wondering when it was going

to stop. That was the longest of the tremors, and the strongest of the

tremors.

That night we didn't really sleep because you were sort of hearing these

distant tremors all the time.

The next day, the Saturday morning, the Officer-in-Charge of the police

station, Sergeant Mark McCardie, rang me up and asked would I attend

the police station and give a briefing to Chief Minister Hatton, about

events up to that stage - where we thought the epicentre to be and what

the probable damage could be.

We still weren't sure of its exact location. I advised the Chief Minister

that we believed the most important thing in the general area was the

gas pipeline, and that N.T. Gas had said, "You've got a fortnight's

gas left in the pipeline, from Tennant Creek to Darwin, that's useable.

After that you may have to change to alternate fuels if the gas line

is affected.'

Chief Minister Hatton returned to Darwin at 11 a.m. that morning, and

it wasn't until 2 p.m. that afternoon that a helicopter, which N.T.

Gas had chartered from Alice Springs, arrived. They said there was a

funny looking dark line about five Kms south of Lake Surprise running

across the gas line. They were going to investigate by road. This was

done late Saturday night, but no-one found the fault line until the

Sunday morning.

On the Sunday morning I was out in the area as well. We were driving

along, and I'm trying to think whose bulldozer has been along the road

and pushed all this dirt up - unbeknownst that this was the earthquake

fault line.

After following this for a couple of kilometres we thought we'd better

stop and have a good look at it to see who'd been out here.'

What we saw was that the Alice Springs side of town had pushed closer

to Tennant Creek resulting in a big mound of dirt. By this time we'd

got to the area of gas line. When we got there, there was this big heap

of dirt across the top of the gas line, which was the fault line, right

through the middle of it.

Immediately N.T. Gas asked that the area be completely cordoned off

and evacuated, and no-one be allowed within ten miles of the pipeline.

At this stage there was still fourteen thousand p.s.i. in the pipeline,

working under full pressure. The immediate thing then was to make it

safe.

N.T. Gas sent the helicopter straight back to Wauchope to turn off the

major valves in the pipeline, then they went straight to Warrego Mine

and turned off the valves cutting the gas off to Darwin at that point.

On the Saturday night they lit the gas line at Warrego to burn off the

excess pressures of the gas, and then on the Sunday they started digging

alongside the pipeline, well back from the fault line, to relieve what

they believed could be pressures on the pipeline.

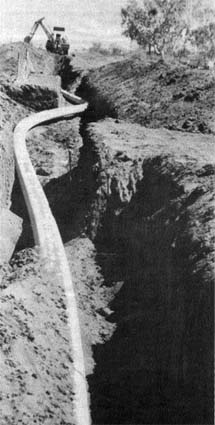

As they dug these hundred metre trenches either side of the pipeline,

the pipe started to distort into massive bows! They then knew the problem

was there and it was going to take some time to solve. More heavy equipment

was taken to the area. Big excavators were brought into the area, and

slots were dug back along each side of the pipeline for some three kilometres

either way to relieve the pressure on the pipe.

Finally, when the pipe was uncovered at the fault line we found that

a weld joint had folded over on itself, and the pipe had actually folded

up in itself.

How it never broke we will never know to this day. The engineers from

the university told me later me that to compress high tensile steel

of that type would take something like sixty millions tons of end pressure

to do it. And the earth did it in that few seconds.

The pipeline was completely dug out and cut in the next few days. With

the gas still coming and the pressure still decreasing, they cut it

with the boilermakers in flame-proof suits. They were lowered into the

trench for thirty seconds while they made a significant cut in the pipeline.

They were then pulled straight out and another one took his place to

keep the cut going, till they got the pipeline cut and parted.

It had to be done this way because the gas was burning. The workers

were working in asbestos suits in the flames - they were just lowered

in. Thy would cut as much as they could with the gas burning around

them and were then pulled straight back out again. They were given massive

drinks of cold lemonade to stop the dehydration of the body and this

continued until we got the fires out.

But while this was going on, mind you, the rumblings were still going

on in town and we could hear them. Every rumbling we heard in town had

to be above 3.4 on the Richter scale. The major ones had gone as high

as 7.4, which is equivalent to any of the big earthquakes in the world

today.

But these fellows worked on in the trenches out there under those conditions,

so you could imagine the nerves - they'd be on end with the nerves.

There was a tree alongside where the fault line was, right near the

gas line. They had dug down alongside the tree. The actual fault line

came from the south to the north on approximately about a thirty degree

angle, heading to the north. And this tree, when they dug down alongside

it, had no roots or base. So they dug back further to see where it had

come from, and discovered it had moved nearly a metre towards Darwin.

That was how much this tree had shifted in the 'quake of 88!

"The end of the world's happening!"

Ross Alley remembers that day

It was in the morning. It was, around about

10 or 11:00 I think and

I was in the old Foodbarn at the time down at the back shelves there

buying some drinks and that to take on the road.

I'd come about half way up the aisle when the earthquake started. All

the shelves started falling in and one of the girls, I think she might

have been a shopper too, grabbed hold of me and said, Hey what's

going on, the end of the world is happening!

Everything was falling down and everyone was pouring out the front of

the shop - yeah and we had to fight our way through all the fallen groceries

and that to get out the front. We just stood there 'til it finished,

Quite a lot of stuff came out of the shelves, yeah, cause it was old

shelves in them days you know and it was all just falling out and coming

all over everywhere, stuff goin' everywhere, yeah.

They were all panickin', they all just rushed out the front. When I

got there they were all standing out on the footpath!

Quite an experience, I'll say!

When I went out the front, I had the old Toyota then, and Auntie was

sittin' in the car and she was panickin'. She said, What'd I touch?

... the car was shaking, shaking, shaking. She said, I thought

I'd touched something and then it started rattling or something!

It was quite an experience. Then on the way out of town we was out near

Phillip Creek and I thought I blew a tyre in the car, it was shakin'

that much but when I got further up the track we realised there was

another earthquake out there. Yeah, so it was quite an experience really,

yeah.

Les Liddell with his

emergency gear.