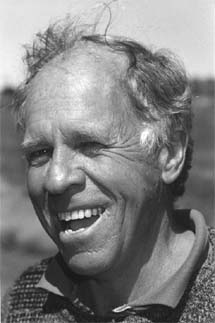

Labour of Love

John Love is a man who enjoys what he

does because he does what he enjoys. If that isn't enough, he's found

his El Dorado too.

He tells us of his early days and life as a geologist

After I left school I didn't quite know

what to do but I was always very keen on geology so I decided on University

- it was a bloody hassle getting into Uni though. I did a course there

on Applied Geology, which is a cross between mining engineering and

geology.

During that time I had a student job at Mt Isa and when that finished

I hitched a ride on a truck which came through Tennant Creek on my way

back to Sydney. This was in the early sixties. I never knew Tennant

Creek existed or that anything like it did - it was pretty primitive

in those days.

We arrived in a big road train which dropped off a shipment of lime

at this little mine called Peko. I was fascinated by that, so the following

year I wrote to the Geology Section and was lucky to get work with Peko

Mine as a student geologist. I thought what a fascinating place.

After Uni I did a year with the Mines Department in N.S.W and then came

here and joined Geopeko. I was in the field for most of the time and

was underground geologist at Peko for about six months. This was great

as it showed me the insides of an underground mine and taught me to

think in three dimensions.

I began to think about ore bodies and the origins of rocks - it's a

fascinating geological story here in Tennant Creek. I was here was between

1966 and 1969 and then decided it was time to go overseas.

I resigned from Geopeko and went down to Sydney. I was about to get

on a boat to go to South Africa when I got a phone call from the Chief

Geologist here at the time and he asked if I'd do another job they had

in Tamworth, northern N.S.W. He said they had just got onto a scheelite

deposit, which is tungsten, and we'd explore that.

I thought, "Oh yeah, what's another few months?". So I went

up to Tamworth and worked on the Attunga scheelite deposit for about

six months or more. After a couple more small jobs I resigned again

and finally got away to South Africa.

I spent a year in South Africa working on the O'Okiep copper mines up

in the North West corner of South Africa in Namaqualand. That was also

fascinating, it was similar geology to here, except that the country

rock was high grade metamorphics and the copper bodies were in diorites

whereas here they're in the ironstone.

It was a real adventure, I was with totally different types of people

and apartheid was then in its hey day - it was a real shock to my system.

After twelve months there it was time to move on so I went to Rhodesia

to have a look round. I got a job for the first six months in a major

underground nickel mine, then I worked on a couple of gold mines where

they had gold in quartz. Coming from Tennant Creek, where I'd been used

to gold in ironstone, I didn't realise the value of gold in quartz.

I did a year there until I thought it was time to move on again.

I didn't know much about porphyry copper, which was a particular type

of low grade disseminated copper deposit that we hadn't then found in

Australia. One place they were found was in South America, so I hopped

on a plane and flew over to Argentina.

I then got the train across to Chile, over the mountains and across

the Andes - that itself was a fascinating experience and also being

thrown in the deep end without speaking any Spanish. At that stage Chile

was going through a pretty turbulent time. Allende had just got into

power and things were unstable.

I remember going over the border into Chile and the Chilean guards came

onto the train and I had to pay $10 a day for every day that I was in

Chile and I only had $50 left. I had to get a job within that time so

I thought I'd give it a go and I paid up my $50 which then allowed me

five days to get a job!

At that time no one who wasn't a Chilean were getting jobs. I went along

to the Embassy who gave me a few addresses and then went to what was

then the Geological Survey of Chile. I arrived on the door and said,

"How about a job?" I couldn't believe it when I got one!

I was in Chile for a year. I was first sent up to the Northern part

of Chile, up in the Atacama Desert and was working on porphyry coppers

there - large low grade copper deposits. That went on for six months

and about that time they had the coup, when Allende was deposed. It

was a very frightening experience. I'll never forget the several days

when we had to get back from the northern mountains and through several

road blocks, back to the city of Antofagasta.

I hid in a house there while they were shooting all around and the tanks

were rumbling up and down outside and the machine guns were chattering

away on the next corner. Helicopters were flying over and the search

lights were going. I'll never forget that.

A couple of days later the Army decided to flush out everyone and being

a 'Gringo', a non-Chilean person, it was pretty frightening. Luckily

on that particular day I thought that I must get word home to my parents,

so I went down to the Post Office and sent a telegram. It was just a

sheer fluke because while I was out, the Army went through the house

and if I had have been there I would have been caught up in goodness

knows what.

Anyway I survived and things got back to normal. I was then sent down

to the south end of Chile and worked on porphyry coppers again. That

was in the most beautiful country I'd ever been - mountains, ice and

snow - a bit like New Zealand except more so. By then, my year was up

and I thought it was time to move on again.

The next six months I spent touring around Europe and eastern Europe

with Michael Pepperday who used to be underground surveyor at Peko.

I'd been in contact with Geopeko back here in Australia. After Europe

I returned and rejoined them and spent three or four years over in the

West, exploring mostly up in the Pilbara area, around the then new Telfer

mine,

Peko went through a financial crisis in about 1979 and I decided that

it was time to go out of my own.

My aim was to find for myself a major deposit of either very fine grain

gold, which they'd been finding in Nevada at that stage, it was called

the Carlin deposit, or a scheelite deposit, like the Mittersill scheelite

deposit in Austria. I don't reckon anybody had really looked seriously

for either of those deposits. So I started out looking for them. I did

a lot of research in all the States then I set off in the field, following

up that research.

I started in N.S.W and went all over, trying to find these deposits.

I worked myself into Victoria and then all through South Australia,

all the time living in my vehicle which I had fitted out for camping

and prospecting. I then worked all the way through Western Australia.

There were several places where I found these deposits, or indications

of them, but everywhere I went I was hampered by the legal system of

Exploration Licences, where the big companies and others take up Exploration

Licences which cover vast areas of Australia. This ties up the ground

and no one can take any leases on that ground. Everywhere I went I was

frustrated by these Exploration Licences.

That saw me round to the Top End of the Northern Territory, to Darwin

and by that stage I was broke. Somehow or other I got into the sand

and gravel business in Darwin. Palmerston was just taking off then and

they wanted roads everywhere. I found out that I could peg an Extractive

Mineral Permit on sand or gravel without worrying about Exploration

Licences, so that was fantastic.

It opened up a whole new field for me and that kept me alive for many

years in the Darwin area, supplying sand and gravel to the Darwin industries.

Of course I never knew there was any difference between sand or gravel,

but in fact there are dozens of different types of sand and gravel!

It was great because it got me back on my feet again and it got me into

the industry and in about 1983 I started chasing gold again. The way

it happened was that I was on an Australasian Institute of Mining and

Metallurgy excursion which they have every year on the Queens Birthday

weekend in the Pine Creek area.

I was talking to a chap on that excursion and he told me that they used

to get gold out of the old uranium mines in the South Alligator River

area and that there used to be a battery out there. When that excursion

finished I went and had look at the mine and found where the old battery

was and found there wasn't any gold in it but then I went up to UDP

Falls.

Just on the side of the road there was an old tailings dam and it had

about 5000 tonnes in it. So I stopped the car and went and had a look

at it, took a couple of samples and panned them down in the South Alligator

River. To my utter amazement they were full of gold, it was just incredible!

That was in the then proposed Kakadu National Park and I couldn't peg

a lease on it but I knew under Section 178 of the Mining Act, you could

actually get an authority to mine it. So I applied for an authority.

I'll never forget the Mines Department officials just laughing at me,

saying I'd never mine those tailings, they were uranium tailings in

Kakadu National Park. Nevertheless after several years of bureaucracy

and all the rest of it, we did a deal with Pacific Gold Mines and they

actually set up a plant at Moline and transported the Moline and Rockole

tailings into that plant for processing. That gave me a bit of cash

and I was back on my feet again.

Following that was a fantastic couple of years for myself and my partner

Garry Hamilton, looking for gold and pegging leases. During that time

I always had in mind that the Eldorado tailings were here in Tennant

Creek. We did a deal with Peko, giving us the rights to mine these tailings.

That must have been in about 1987. Several years later we started mining

the tailings - some of the original battery sands were quite rich, two

or three grams per tonne.

We leached them for several years until 1994, during which time I also

scraped up and treated all those tailings that had accumulated down

the hill, one kilometre away on Joe Schmidt's land.

About that time, I and my partner decided there wasn't enough gold in

it for the both of us so we split up and he went to N.S.W and worked

on slate mines and that sort of thing and I've stayed here ever since.

After the sands finished I had 50,000 tonnes of slimes on the top of

the hill and I had to work out how to mine them.

I finally came up with a method whereby I shoot them down the hill with

a high pressure water cannon, with a trace of cyanide added, then pump

the tailings over the hill to my tailings dam. Every night I run the

solution through my carbon columns and extract the gold onto the carbon

and then periodically strip the carbon and extract the gold.

About a fortnight ago I finished the Eldorado tailings and now I've

commenced cleaning up. However I still have a couple of small dumps

to treat but they are very difficult because they are extremely fine

grained and high in copper, so I may be here for a while yet.

What makes a prospector?

Geologists do the research first and learn

all they can about an area. They'll go out and look at the rocks and

try and interpret what the rocks are trying to tell them and figure

out where the ore came from and where it is likely to be now.

They commonly take geo-chemical samples to send away for assay for things

like gold and other elements like copper, arsenic, tungsten etc, that

may occur with the gold. But the problem with this is that you've got

to pay to get the samples assayed and if you're taking a lot of them

it becomes a significant cost.

Of course it's easier for a geologist who's with a company and can afford

this then follow up with drilling. I couldn't afford this so I had to

go right back to basics and learn the old art of prospecting again.

I had to become a prospector like they were a hundred years ago. I learnt

to be able to detect minute amounts of gold, down to one part per billion,

in the pan. The gold had to be free gold but invariably if it out crops

on the surface, the rock weathers and the gold is released as tiny free

particles. I taught myself to pan, down to these incredible amounts,

which I suspect the assay laboratories then couldn't detect at those

levels. That was my main method of exploration.

I went to a place in Western Australia that was reputed to be a fine

gold (Carlin) deposit way out in the Gascoyne.

After speaking to the Geologist in charge, who said there was no visible

surface gold, I walked over the hill and took five samples from the

surface soil and panned them using my techniques and each one of them

had gold in it!

From that moment on I knew I could find a Carlin fine gold deposit if

it outcropped on the surface and from then on that was my main method

of exploration. It cost me nothing except effort and the water that

I'd carry with me. I reckoned doing that, as crude as it was, I could

still compete with the companies because I was actually there in the

field doing the work, not sitting in the office dreaming about it!

You just have to switch your eye in to look for that tiny, tiny speck,

it's almost microscopic, but when you get the sun on gold, it glints

like a piece of a jewel. It just needs that extra look to be able to

do it!

The old leach vat

used as a water reservoir.

Blasting away at the

tailings with the water cannon to put the tailings into solution.

The atomic spectrometer

measures the amount of gold in solution.